Women on strike!

- anne

- Mar 3, 2023

- 7 min read

With International Women’s Day on the horizon and strikes happening across the public sector, it seems rather apt to take a look at women’s place in the history of strike action ... which is how it all came about in the first place. The struggle for equal rights – in the workplace and elsewhere – is well documented, with many successes – and some setbacks. But let’s look beyond the binary, at the big picture and collective nature of social change – as Audre Lorde famously articulated:

The revolution is not a one-time event.

The right to strike, to demand better conditions, pay and equality is vital to any progressive society – no wonder the UK government is desperately pushing through draconian legislation in a Thatcherite move to curtail opportunities for industrial action. Preventing ‘essential’ workers from striking and threatening them with the sack, does little else but emulate other regressive attempts – attacks on our right to protest and ‘overhaul’ of the Human Rights Act - to turn this country into a surveillance state. And while trade unions are far from perfect, let’s not lose sight that they have brought many benefits to our lives. We would not have a five-day week, paid holidays or sick pay, things many take for granted and are up for grabs as the gig economy digs in its heels, without trade unions. And it’s never been more important to join a union!

Matchgirls strike

Over the winter break, I watched Elona Holmes and the sequel Adventure Strikes Again (nice pun!), in which Enola finds herself in the midst of none other than the Matchgirls. Finally, a mainstream film pays tribute to these trailblazers.

Abysmal conditions, in the 1880’s, were the norm. People living in abject poverty with zero rights rarely spoke up to make demands – too scared to lose the little they had. The situation at the Bryant and May factory, in Bow, East London, wasn’t any different … until the day, women and girls decided they had had it.

The working environment at the match factory was particularly dire and dangerous. The use of white phosphorous in the production of matches caused an extremely painful, disfiguring and eventually fatal form of bone cancer, known as ‘phossy jaw’. Workers were mostly girls and women aged between 15 and 20, many of Irish descent. Not only did they put their health and lives at risk, they earned pitiful wages for long days and faced fines for extra toilet breaks and untidy workbenches.

The huge profit margins enjoyed by Bryant and May did nothing encourage them to implement any changes … until they went too far and dismissed a worker, sparking off a rebellion. The story got picked up by activist Annie Besant, who published a damming article comparing the factory to a ‘prison house’ centring on women’s voices and their harrowing experiences. Bryant and May’s initial response was to force the women to deny their daily reality. The women refused and staged a walk out. In one of the scenes from the film, strike leader Sarah Chapman stands on a table and shouts: “It’s time for us to refuse to work. It’s time to tell them – NO!”

They stopped work for three weeks and they WON! The factory owners agreed to almost all of their demands and recognised their union. Central to this story is the role and agency of the women workers themselves who were driving the struggle and provided great impetus for other labour activists to organise. It was a truly ground-breaking moment in the history of trade union and women’s rights – that still resonates today.

Leading feminist voices

Women’s involvement in the trade union movement predates the Matchgirls strike by a few years. Feminist activist, Emma Paterson, inspired by a trip to the U.S., where she visited all-women unions like the Female Umbrella Makers’ Union, founded the Women’s Protective and Provident League (in 1874), which soon became the Women’s Trade Union League. A year later, she became the first woman Trade Union Congress (TUC) delegate.

1888 was a big year for women’s rights organising. Clementina Black, another feminist trade union campaigner, moved the first successful equal pay motion at the TUC for equal pay for equal work. She was also involved in supporting the Matchgirls strike.

"...women are unorganised because they are badly paid,

and poorly paid because they are unorganised.".

Mary Macarthur

There are many herstories of strikes up and down the country, but few that are etched in the public psyche, which is partly why it is so easy for the ‘ruling classes’ to erase and restrict our collective power. Think of the women chain makers of Cradley Heath in the Midlands, literally breaking their chains. They staged a 10-week action (1910) against low pay and sweated labour, led by trade union activist Mary MacArthur, founder of the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), they also won – finally getting paid the minimum wage.

Bermondsey Uprising

On the strength of that victory, Mary Macarthur made her way to Bermondsey where Ada Salter, the social reformer, had founded the local branch of the Women’s Labour League (WLL). Bermondsey, one of the country’s poorest areas, had become the site of budding socialist activism. The WLL demanded votes for ALL women and promoted women candidates for local council elections. In 1909, Ada Salter stood for election and became London’s second female councillor. She was also actively recruiting women in the local factories to the NFWW.

Bermondsey’s workplaces were heavily gendered. Men worked in transport, engineering, printing, dock work or the leather industry, and women’s labour was mostly concentrated in the processing and packaging the raw materials - tea, sugar, grain, and spice - that arrived at the docks from colonised regions around the world … exploitation from beginning to end, just so a few could make the big bucks. Workers generally earnt a pittance – and women a lot less than men.

By 1911, however, unrest was brewing. Tramway workers were striking, demanding better conditions; and men in other occupations soon followed suit. This led to spontaneous solidarity action by women - even though they weren’t unionised. Mary Macarthur, who had come to london to support the Idris lemonade women’s strike - sparked by the sacking of Annie Lowin, a 25-year-old mother of 2 who had been working for the company 13 years! – felt encouraged by the level of organising. In August things ramped up, inspiring women beyond Bermondsey, where 15,000 women were striking. By September they had claimed victory!

Women’s Trade Union membership increased by 160% during WWI, when two million women replaced men in employment and new jobs were created for women in areas such as the manufacturing of munitions. But as soon as the war ended, women were relegated to their pre-war roles and, as the UK economy was plunged into recession during the 1920’s and 30’s, opportunities vanished. Even trade unions, who had been at the forefront of campaigns for wage equality – and opportunistically used this to recruit women members - withdrew this important demand to protect ‘men’s work’!

Unlike the post-WWI years, the 1940’s and 50’s marked a period of unprecedented economic growth and demands for an expanded labour force … so guess who the capitalist system enrolled? - women and migrant workers, of course! Trade union membership among women increased substantially – reaching 2.5 million (29% of all women workers). But the white men in charge couldn’t care less about the rights and demands of women and members of colour.

Made in Dagenham

Fast forward to 1968 to the day women machinists at the Dagenham Ford factory find out that their jobs had been reclassified and downgraded from skilled to unskilled, and that they were now earning less than men doing the same job! Well, that went down like a lead balloon. They decided to walk out, demanding equal pay. The strike brought the factory to its knees - no-one else had the specialist skills to make the seat covers - and management were forced to negotiate. Such was their persistence that in the end, Labour Employment Minister, Barbara Castle MP, got involved, leading to the Equal Pay Act 1970. You could argue of course that more half a century later, the gender pay gap is still very much on the agenda! Really recommend (re-)watching Made in Dagenham.

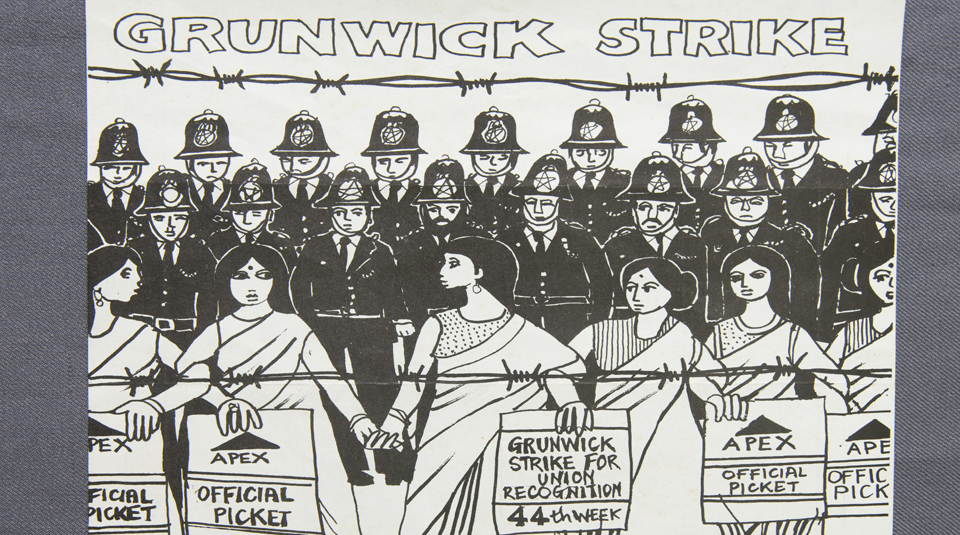

Grunwick dispute

Migrant women workers faced then – as they do now - double the discrimination, and many jobs -even those classified as ‘women’s jobs’ - were out of reach to them. In the 1970’s and 80’s, South Asian women, who had migrated from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, or East Africa, were forced into the lowest paid manual or factory jobs – such as those at the Grunwick film processing plant in Willesden, north-west London. But, in the hot summer of 1976, enough was enough.

When Jayaben Desai walked out in solidarity with a colleague who had been sacked, others followed. And as her manager compared her and her colleagues to "chattering monkeys", she gave him a piece of her mind: "What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr. Manager." And so began a two-year dispute for better conditions and union recognition.

The strikers attracted widespread solidarity from activists who joined them on the picket lines outside the plant, as well as other workers, including postal workers. In June 1977, during a ‘week of action’, the police deployed a paramilitary police unit – for the first time in an industrial dispute – and violently quashed the 20,000 strong demonstration.

While the strike was unsuccessful per se, it played a significant role in exposing racism, misogyny and ageism in the labour and the trade union movement in Britain and helped rallying workers of different genders and ethnicities. Long term, it improved working conditions and the recognition of migrant workers – not least the role of Asian women in the economy and trade unions. Importantly, it will continue to inspire others to stand up against injustices – like those who led the industrial action against Gate Gourmet, in 2005.

As strikes rage across the UK this month and beyond, we are once again reminded - A luta continua!

Comments