Simp_Lee Miller

- anne

- 9 hours ago

- 3 min read

One by one galleries are now showcasing work by women, who, for far too long, had been living in the shadow of powerful men.

Think Dora Maar (and Picasso) or Dorothea Tanning (and Max Ernst) - both pictured below: Dora Maar, Paris, 1956 and Dorothea Tanning, Huismes, 1955. And now, finally, we get to see the extensive catalogue of Lee Miller’s work (Man Ray/Roland Penrose).

If you make it to Tate Britain before the exhibition closes on Sunday 15th February, you will be dazzled - as much by the sheer volume of work on display, as by the quality, creativity and diversity.

As well as the sheer beauty of the art work and the truly iconic nature of Lee Miller herself - stunning, in an androgynous kind of way, charismatic and fearless in equal measure - I loved her clarity and ability to use her own agency to take control of her life and her art.

"I'd rather take a picture than be one"

She quickly moved on from a modelling career to become a photographer - moving from passive object to actual creative agent. In some of her self-portraits published in Vogue, she was credited as model and photographer - possibly a first.

In the summer of 1929, at 24 years old, she packed it all in and headed to Paris, where she met Man Ray. They began working together and produced some outstanding, very experimental art - pushing the frontiers of photography to explore love, power and desire - subjects largely considered taboo, as well as trying new printing techniques. Here too we get to witness that fluid transition between muse and co-creator that is so Lee Miller.

Looking at the pictures on display, it’s almost hard to fathom that this is pretty much the inception of the popularisation of photography as an art form, and certainly of surrealist photography. So much so, it has often been contended that their relationship changed to course of art history.

As you meander through the various rooms - travelling to Egypt, where she briefly lived with her then husband, to New York, where she worked with Gertrude Stein, and back to Europe, where she photographs famous friends, many in surrealist circles - you get a glimpse of her immense talent.

When WWII breaks out in 1939, she’d just joined surrealist artist Roland Penrose in London. Being a US citizen made her ineligible for war work, so she went back to Vogue where she became the leading photographer.

And here’s an interesting nugget of information. The British government saw women’s mags as a propaganda tool - suprise, surprise! - to boost morale, inspire women to adopt clothing restrictions and short haircuts, which Miller helped popularise, and encourage women to enter the workforce.

Censorship was obviously rife - but did you know that for reasons of morale and national security, images depicting bomb damage should show at least 50% of undamaged material?

But all this time, Lee Miller was itching to become a war correspondent, and eventually, she did. In late 1942, she was embedded with the US Army, but it took some sheer determination to break down the barriers she faced as a woman getting close to the frontline.

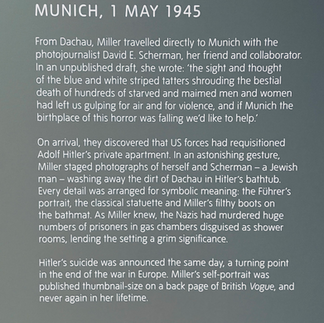

She spent several years documenting the atrocities of war, often being first on the scene, witnessing horrific scenes, not least in Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps.

Driven by her fierce opposition to fascism and drawing on her surrealist flair, she produced her most poignant work. But what she witnessed left an indelible mark and her interest in photography waned over time.

She hid her work - roughly 60,000 - in an attic and turned her attention to gourmet cooking. Thankfully, her son, Antony Miller, found the treasure and co-founded the Lee Miller Archives and The Penrose Collection.

If you have the stomach to battle the crowds - you should absolutely go.

Comments